For Indigenous people ochre is a precious resource.

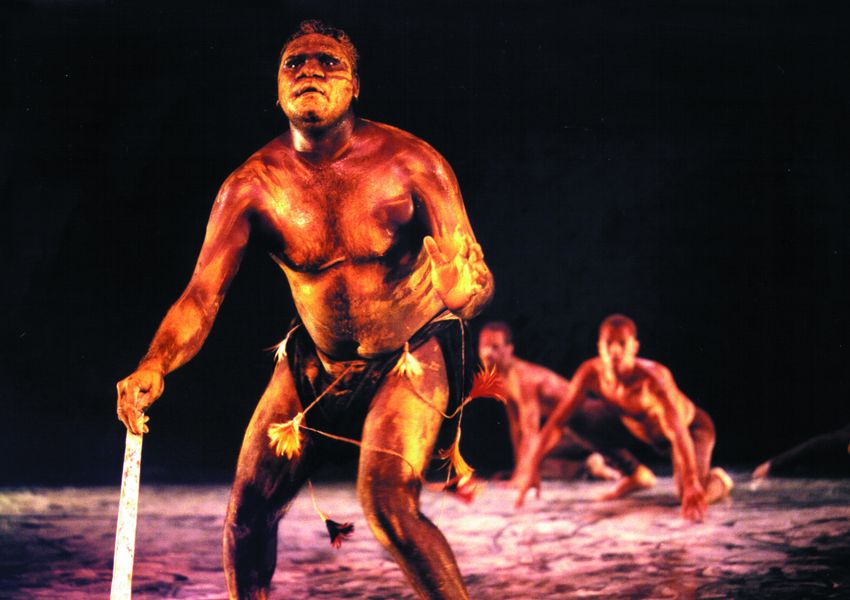

Through ochre runs a tactile imprint of all that is sacred, of all that connects people to their Culture – the past, present and future. Ochre resides in the Land, absorbing the Earth’s history through millennia, until people extract it, mix it with other earthly elements and use it to be one with the Land. They use it to tell their story, to practice their ceremony, to feel its transformative texture on their skin and they use it medicinally.

Ochre has been mined by Aboriginal people in quarries and pits across Australia for many thousands of years and it continues to be excavated and processed for art making practices and ceremony. There are over 400 recorded First Nations’ ochre pit mining sites across Australia. Most mines are open cut - some are quite small operations while others are up to 20 metres deep. Ochre is extracted with stone and wooden tools as rock particles or compressed clay, which is then crushed and mixed with a fluid such as water, saliva, blood, the fat of fish, emu, possum or goanna – or occasionally orchid oil - to form a fixative so that pigment can be painted on rock, weapons, ceremonial objects and skin.

The common usage word ‘ochre’, comes from an old French term ‘oker' or 'ocer’ meaning ‘pale yellow’ but has evolved in the English language to refer to any pigment that is derived from the processing of minerals and mineral aggregate (rock and clay). It should be noted that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander clans and Nations all have their own language words for this substance. For the Yolngu people of North East Arnhem Land, the white ochre is referred to as gapan; for the Noongar people in Western Australia the red and yellow ochre is it is known as wilgee; for the Wiradjuri people in New South Wales, their red ochre is called gubarr or gidyi. And it is different again for the Yawuru people in the Kimberley Region who call the black ash from burning wood gubar, while yellow is known as gumbarri, white as larli, and red is called duguldugul (when used in ritual).

For millennia, Aboriginal people have not only mined ochre for their own use but have also traded it across regions as a valuable commodity. When Mungo Man was discovered in south-western New South Wales in 1974, he was found lying on his back with a covering of red ochre that was not found in that locality.

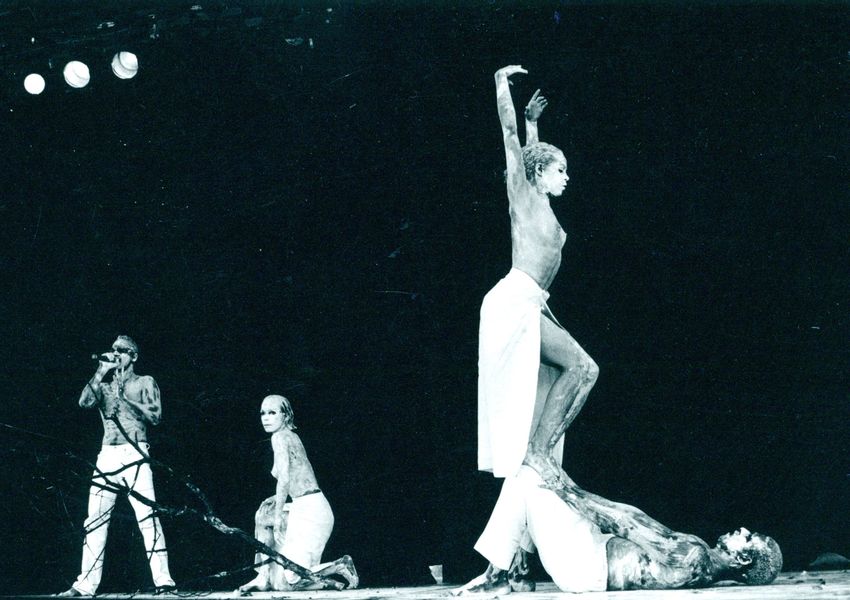

While the most recognised ochre colours are red, yellow, white and black, other colours such as orange, purple, pink and turquoise are also found and used. Each colour is associated with quite specific meaning and use. White is often used during times of ‘sorry business’ and loss; yellow is most often associated with women’s ceremonies; red ochre has many associations but is frequently used where conflict is happening, as well as celebration and ceremony; black pigment is most often derived from coal, and is mainly used for men’s business. The patterns that are drawn on the skin with the ochre are also very purpose specific and are exclusively the cultural property of each clan. In this way the drawing can be ‘read’ for a clear understanding of the story being told or the ceremony being conducted.

Ochre is also widely used as medicine. When ingested, some ochres have an antacid effect on the digestive system, while others are rich in iron with reports that consuming such ochre can assist with lethargy and fatigue. Red ochre, due to its rich mineral content, is often used to protect the skin from the elements of weather, insect bites, ticks and fleas and is also excellent in caring for wounds. Ochre imbued with animal fat is also rubbed into wooden tools and ceremonial items to preserve the wood and prolong its use.

In 1963, the Yolngu people of North East Arnhem Land sent a ground-breaking document to the Australian Parliament. Presented on bark and adorned with traditional ochre designs, the Yirrkala Bark Petitions, are one of the most significant actions by Aboriginal people in modern history.

Written in Yolngu Matha (Gumatj dialect) and English, and providing critical information about the Yolngu people’s ongoing and unbreakable connection to the land surrounding the community of Yirrkala, the petitions were tabled in the Federal Parliament in August 1963. Their purpose was to negotiate a land rights decision against a particular mining company and in favour of the Yolngu people. The claim failed, however these petitions have been referred to as a foundation document of Australian constitutional reform due to their significant contribution to the land rights movement as well as the success of the 1967 Referendum which changed the constitution to recognise Australia’s First Nation People’s rights. The petitions remain on permanent display in Parliament House in Canberra.

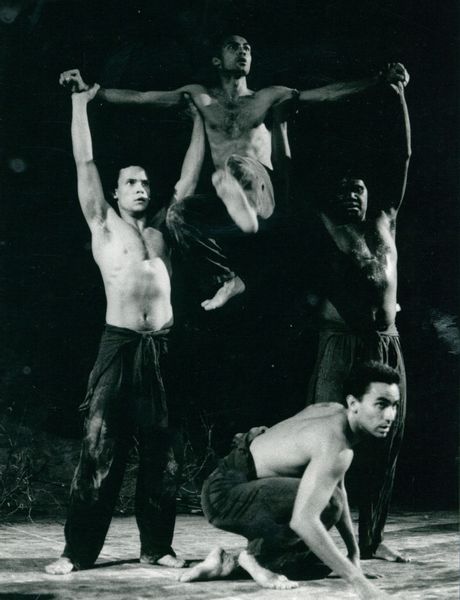

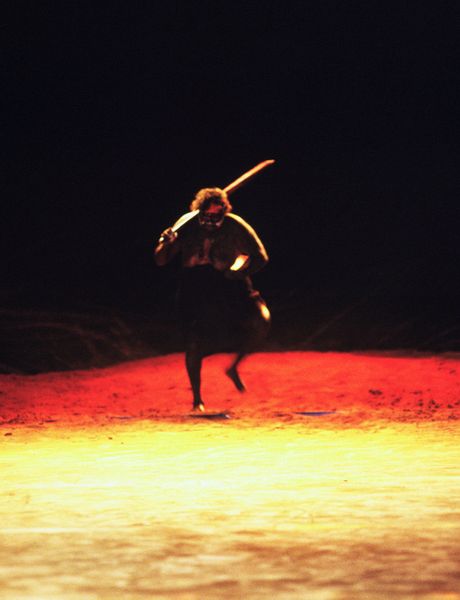

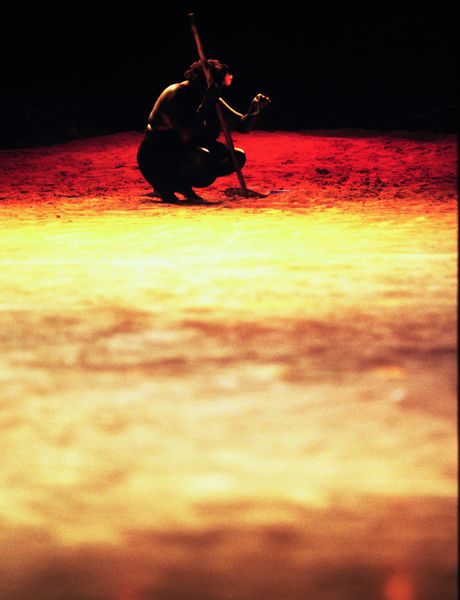

When Bangarra moves into a theatre (in ‘theatre-talk’, this is known as ‘bumping in’) to set up for a season of several weeks, or even one performance, the first thing that happens is the laying down of many meters of heavy-duty plastic in all backstage areas. A designated space is allocated as a ‘paint up’ area which the dancers use exclusively for this purpose. ‘Painting up’ prior to the show, is a pre-performance preparatory ritual, helping the artists focus and transform themselves into the elements and characters of the story. The use of a single paint-up area ensures the theatre can be quickly cleaned post show or season. As the show is ‘bumped-out’, the plastic is washed and dried, ready to be transported to the next venue.

Bangarra Dance Theatre sources a variety of ochres from various places around Australia for use in its productions. On the Return to County season of Miyagan in 2018, Aunty Diane Riley McNaboe took the company to collect yellow ochre from a traditional ochre pit near Dubbo. This was an incredibly enriching experience for the Dancers. They were able to physically connect to Country, building on the connections already developed through yarning circles and research, thus bringing their artistic endeavours full circle and enabling the synthesis of the physical, cognitive and metaphysical. For the Wiradjuri people, this particular ochre is highly significant for women, and was worn by the Bangarra women in the section ‘Yanhanha’(The Women) in Miyagan.

The beautiful ‘gapan’ (white ochre), often used by Bangarra in performances is sourced from Nuwal ochre pit in Yirrkala (North East Arnhem Land). When the company toured to this area in 2018, the production team were taken to Nuwal were they were able to connect to the Country that had enriched thousands of Bangarra performances.

In any given year, the company will use well over a 100kg of ochre. Bangarra proudly sources the majority of its ochre from community organisations, supporting local employment and strengthening our connections through such contemporary trade. Audiences are often not aware that the ochre they see in nearly every production is a very pure and sacred substance, the same substance that has been used for many thousands of years as a fundamental part of Aboriginal life and culture.

For Indigenous people, ochre is a precious resource. When land is taken and developed for mining, urban development, or mass agriculture, the ochres go with it, along with the source of thousands of years of cultural connection and expression.

Through ochre runs a tactile imprint of all that is sacred ...

A cultural platform for a beautiful exchange

The 1990s was a remarkable decade of political activism and legislative reform, which ignited a period of powerful awakening across Australian society. It was the decade of the Mabo and Wik Decisions, Paul Keating’s Redfern Speech, the Bringing them Home Report and the first Sorry Day. It was a time where cultural information infused contemporary expressions in a way that resonated and shifted perspectives. It was the time when Yothu Yindi‘s song ‘Treaty’ with its message of truth telling and advocacy against a score of electronic and traditional sounds, was at the top of contemporary music charts. It was against this politically-charged and hopeful landscape that Bangarra’s Ochres was created.

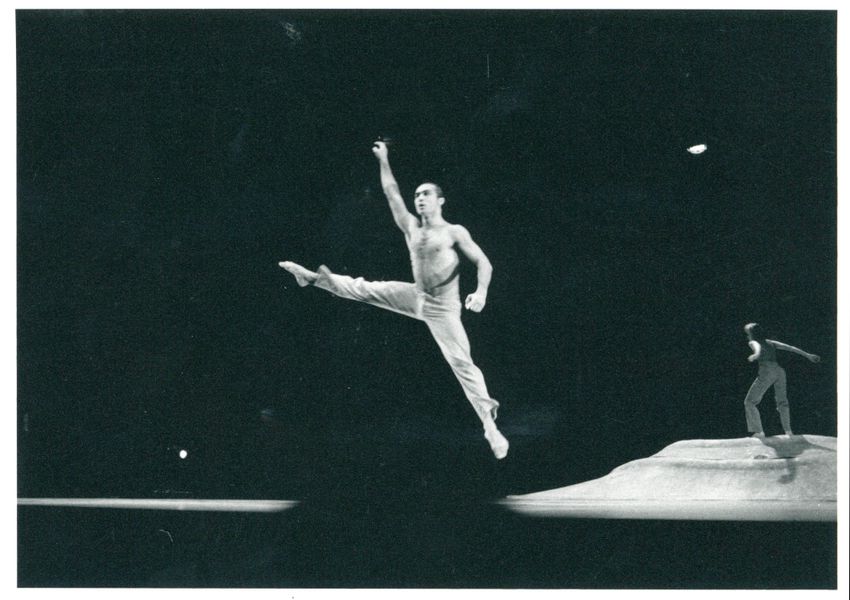

Created in the first decade of the company’s life, Ochres was to become a landmark work that rode with the wave of the 90's socio-political agenda and enabled Bangarra’s voice to be heard. However, it was only with the trust and support of a several key individuals who supported Bangarra’s mission that the creation of Ochres was even possible.

Djakapurra Munyarryun was at the heart of the creative life cycle that supported the making of Ochres. A songman from Yirrkala who carries his Country with him wherever he is in the world - walking both his land and the land of others – he gave Bangarra the bridge for information to be shared and transmitted through creative storytelling in the form of dance theatre.

Mrs Ward (dec), an Elder from the Ngaanyatjarra Pitjantjatjara Yankunytjatjara (NPY) lands was another individual who was an advocate for her people, her culture and her land, and leant her strength in initiating and gathering community support for many projects including early Bangarra productions, such as Frances Rings’ first work for the company Minymaku Inma in 1999. It was with Mrs Ward’s trust and support in the years leading up to the new millennium that Stephen Page was able to bring a large group of Western Desert community members to Sydney to perform in the Opening Ceremony of the 2000 Olympic Games.

Bangarra has worked with many Cultural Consultants over the decades. They are the knowledge keepers who provide a cultural platform and a living connection to the beating heart of the world’s oldest living culture. They are absolutely fundamental to Bangarra’s history as well as its future.

Bangarra proudly sources the majority of its ochre from community organisations, supporting local employment and strengthening our connections through such contemporary trade.

Written by Shane Carroll

-

Author of 'Ochre is of the earth'

Shane Carroll

-

Author of 'Ochre is of the earth'

-

Editors

Yolande Brown

Frances Rings