After training in Japan in track and field and then studying aquaculture, Thomas Greenfield took to dance at the mature age of 21. Serendipity came into play, as he found himself invited to guest with Bangarra on the 2014 production 'Patyegarang'.

It was 2013 and I was working in Brisbane as a guest artist with Expressions Dance Company. One night, after a full day of rehearsing, I was sitting on the couch watching an incredible documentary on The ABC, First Footprints, a four-part series on our country’s history. I turned to my friend and said “I have to dance with Bangarra one day – I just have to!”

The next day, I was walking through Morningside Train Station down to this really great pastry shop and my Nokia burner phone rang – a number I didn’t know – I answer it and this voice says:

"Thomas Greenfield?"

"Yes"

"This is Stephen Page"

"… yes!?"

After studying aquaculture at Flinders University, I got into dance at the age of 21. The first contemporary dance I saw that I really connected with was on VHS in Dance History Class in 2007: Black from Ochres. It’s the first thing I saw that made me feel "You’re in the right place: this is what men are meant to do when they dance on stage”. In 2008 I first met Stephen on the wharf. The next year, while completing my Bachelor of Performance (Dance) at Adelaide College of the Arts, I did a two-week secondment with Bangarra during the company’s creation of Fire.To me, that was the only experience you would have with Bangarra as a ‘white’ dancer.

While I walked through the train station, Stephen explained the concept for a new work. He asked if I would be interested in being involved.

“I’m interested in doing anything that gets me involved with Bangarra!” I responded.

I liked not having to ‘pretend’ to be something

I came in to Bangarra as a complete outsider; even in the studio space I was the one on the outside. I was excited and nervous and had no expectations. I didn’t know how this company would approach a development. I think, for the first two weeks of the development, I just sat on the floor and watched as Stephen was working with the ensemble on the opening scene, ‘Eora'. I got to sit and watch and listen.

"You’re coming from sandstone country. That’s what you’re used to walking on."

From Stephen’s first words, the movement was given physical intention, scribed by the country that this collection of people were coming from. It was informed; the bodies were informed before they started to move; the dancers were filled with intention.

This piece was about language, and the people. In playing Dawes, it was a privilege to play a positive ‘white’ role in regards to black/white cultural relations. Lieutenant William Dawes documented a language, without being asked, purely out of interest and respect: one rare positive influence white culture has had on this country. In the end, he helped to save a language that other men of his era were helping destroy. To play that role was an honour.

Dawes, the man, was open, respectful and interested. He had care for being in this new place and a wanting to understand, learn, share and exchange. In the studio, I felt aware and connected to it all, and excited. Everything in the process made sense; there was intention behind the concept of movement.

I watched while Stephen worked with the ensemble. Then we worked together on a passage of movement where Dawes first steps On Country, on land. I didn’t enter from side of stage with the cast, I entered from the audience and walked down some big old stairs before stepping on stage.

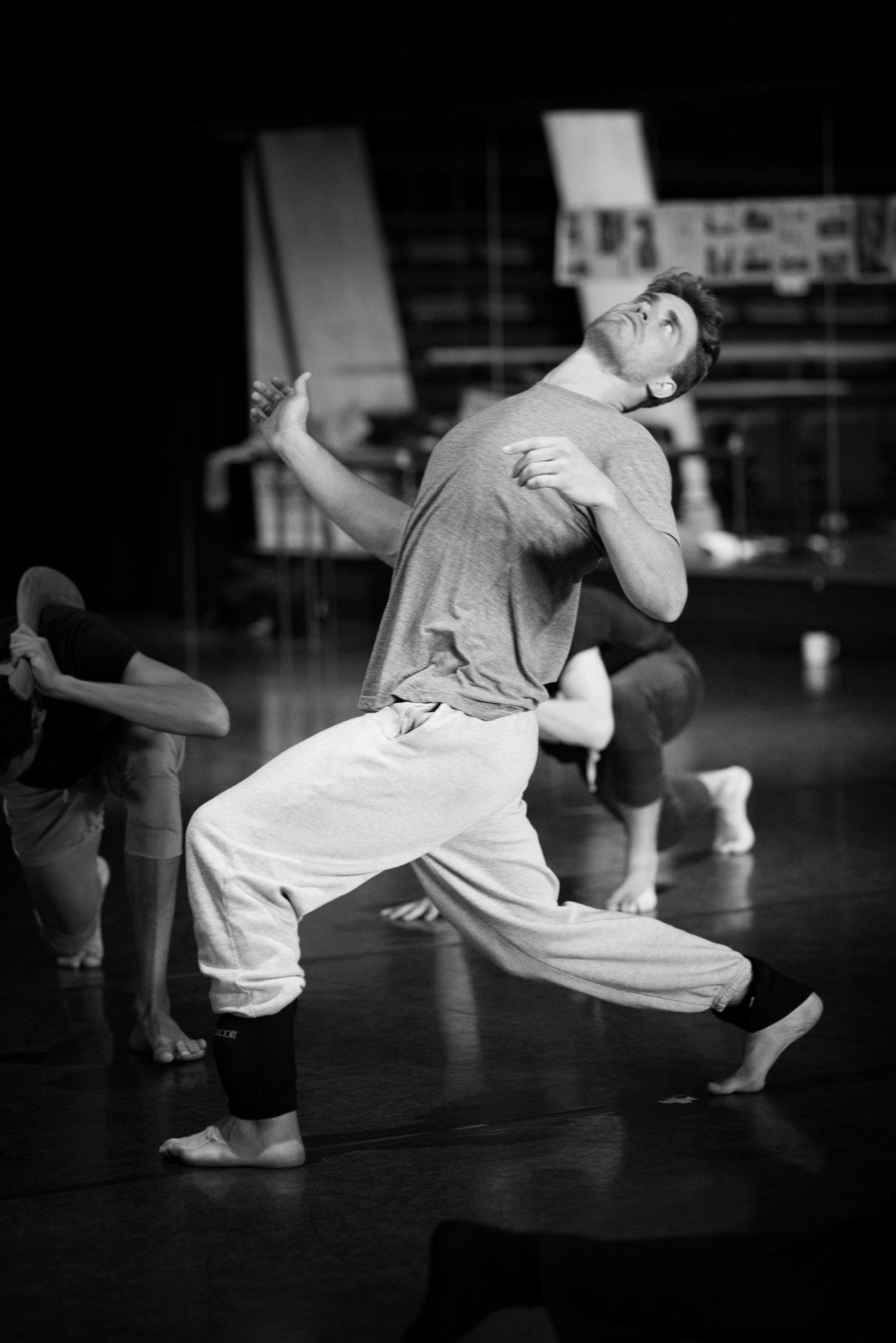

I remember being very apprehensive, creating this first block of solo material, when it was just me and Stephen in the studio. I didn’t yet know Stephen’s movement language, his dialogue, but I had that eagerness to try anything. At first, out of respect and not wanting to forge ahead and offer movement, I waited to hear and exchange, and then transcribe it onto my body. This was nerve-wracking, in a good way. I was learning Stephen’s language, how Lieutenant Dawes would have been learning from Patyegarang. By the end of the creative process I was able to have fluent conversations: I knew how to talk to Stephen in the studio through my movement and trusted that it would be right for the piece as we created more material with the ensemble and duets with Jasmin Sheppard. But when you learn a language, you keep your accent. I kept the difference in a really positive way. I have an inherent way in which I move and that always echoed through whatever Dawes did on stage.

I liked not having to ‘pretend’ to be something: I am a white man and I was working in a black environment; William Dawes was a white man, stepping into a black environment. He didn’t get anything out of documenting the language. He just wanted to be able to understand and be able to communicate. We step onstage as artists, practitioners, dancers to communicate to people. We want to be able to have something understood – even if it’s abstract.

After working with Bangarra, I sometimes ask myself “What would Elma Kris do?” and I’ll brighten my eyes to let the story radiate out or I’ll offer the ‘simple’ gesture. Or I’ll ask myself “How would Waani Blanco step right now?” and then I’ll physically ground myself and move deep in my legs rather than ‘out of and away from the earth’: like Wani with his ‘pelican feet’ stepping. There were these things from my colleagues that made me question how I want to be a mover, be a performer, be a storyteller, but I don’t believe my movement changed after working with Bangarra; it was my approach to movement that changed. My approach became to move with intention.

I can’t really remember the last show. My last day was beautiful. I rocked up and Lenny Mickelo had painted me one of his original universe canvasses; the incredible Elma Kris had left this beautiful dilly bag (that I still use) on my desk; Nicola Sabatino had left me a written card; Kaine Sultan-Babij had gone to a photobooth and photographed his hands in the ‘tidda’-fingers position and framed it for me; Tiff Parker had done a farewell video for me … So, I rocked up and there were all these beautiful things. That’s what I remember about my last day performing with Bangarra.

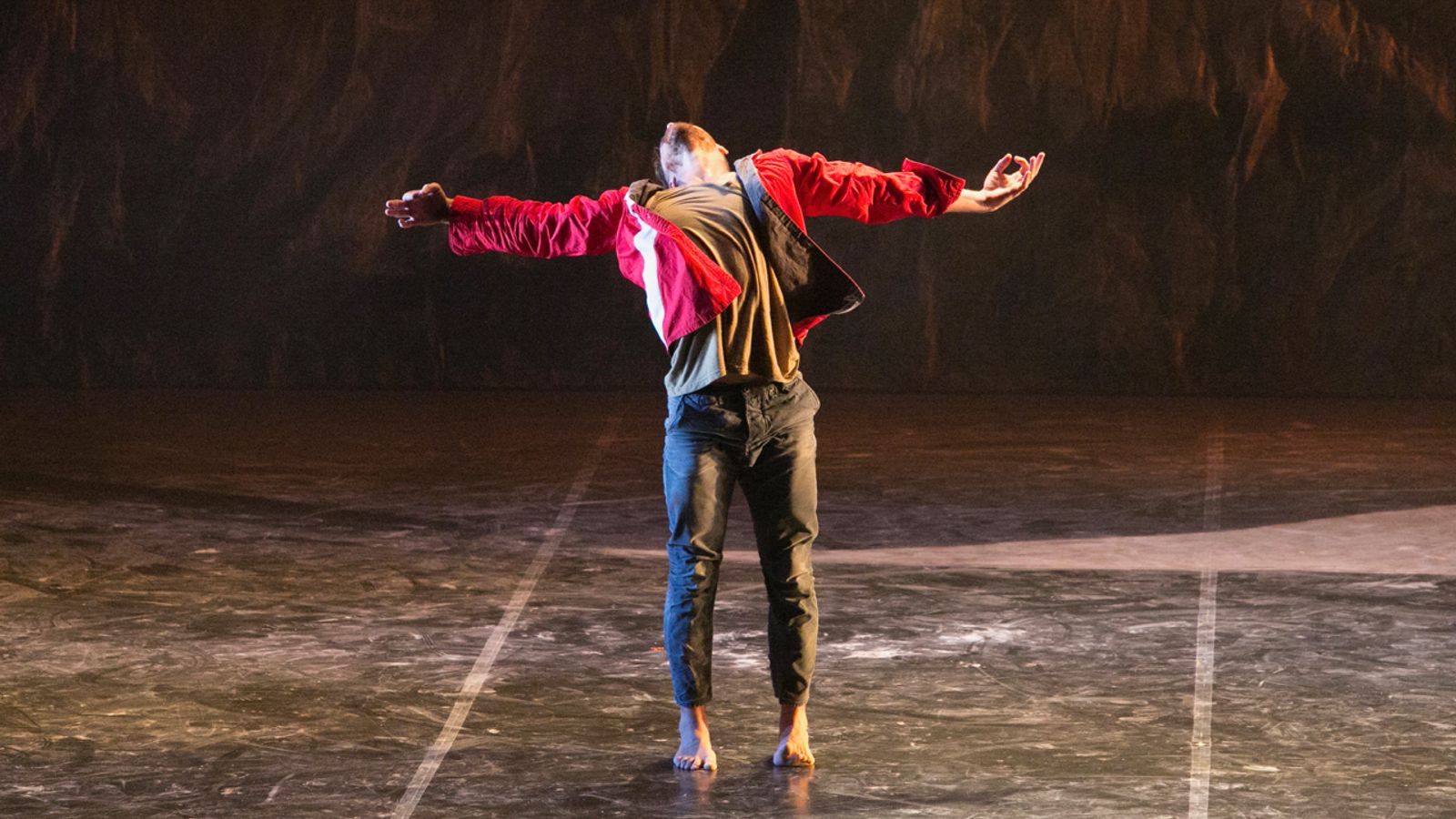

And I always remember the farewell solo for Dawes towards the end of the work, ‘Departure’. When I see it in my mind, I see the darkness in front and feel the light behind, and I feel the weight of responsibility. I feel the weight of acknowledging what was happening at the time – and still is. I feel the responsibility of acknowledging the history of what’s happened/happening On Australian Country and the weight of responsibility as I carry this for the company. All this, while still having pride: being proud of being a white Australian man and also proud that I could tell a story with a First Nations black community, for them.

For me, Patyegarang was the most holistic, honest workplace experience I’d had, where the integrity in the story telling was unquestionable because it happened: this was the telling of our history. It was also the right time to amplify the things that were smouldering in me and amp up that ‘fire’. It was my dream!

'Patyegarang' was the most holistic, honest workplace experience I’d had

Article by Yolande Brown

-

Dance Artist

Thomas Greenfield

-

Dance Artist

-

Author

Yolande Brown