Look at where we work, we're here on Eora land.

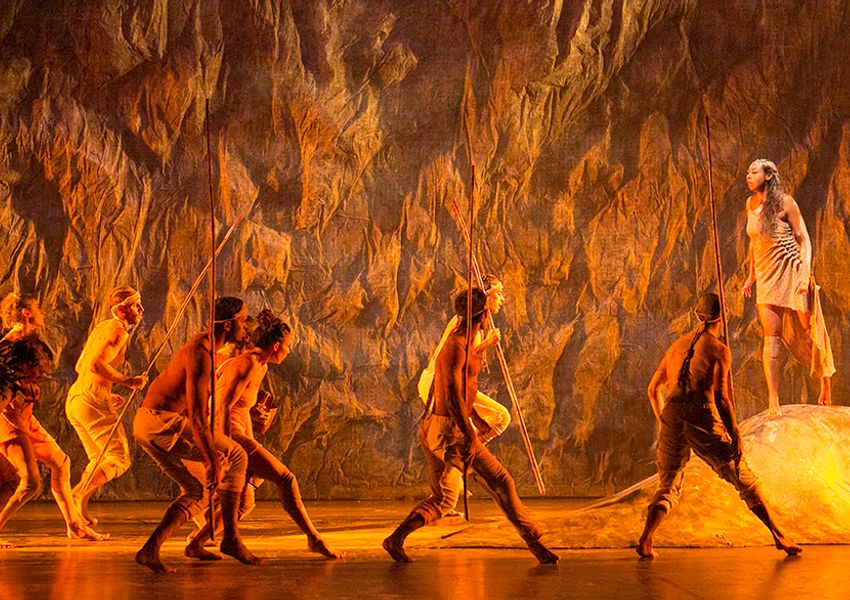

Patyegarang made me start to see the world differently like I did out at Lake Eyre for Terrain, but this time in an urban environment. You have to strip back what you're seeing, so you don't see the urban sprawl. We took a trip out with all the dancers on a boat. It wasn't the first time I'd done that, but it was the first time I realised how important the water is, how important the rocks are, and what the harbour means, those two protective gates that have stood there for so long. I didn't have to go far. I just needed to open my eyes.

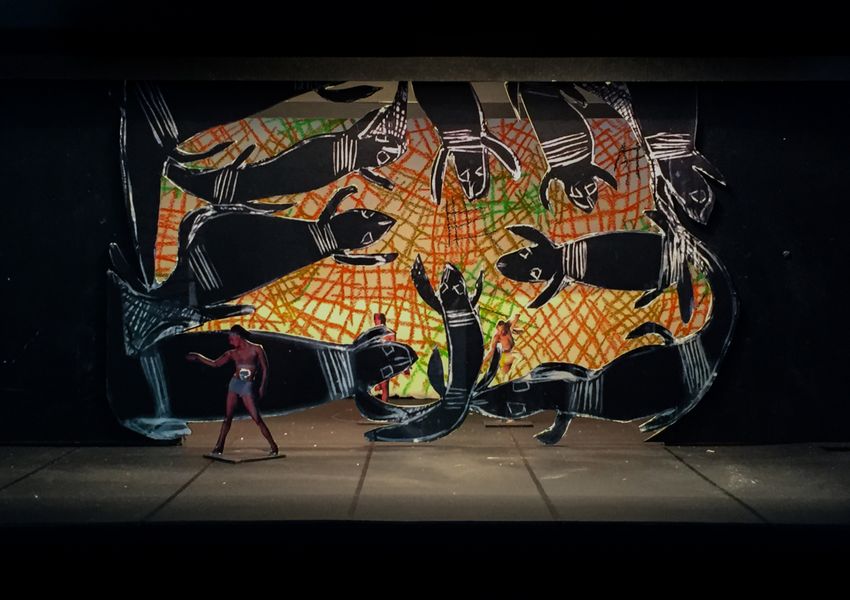

I ended up creating this sandstone wall out of linen. I added a mixture that gave it strength and rigidity. I crunched it together, pulled it, stretched it, put it back together. In the end it came out as this beautiful, crinkled, semi-hard cloth, which I gave some treatment to with paint. That became the key driver for everything else.

Normally there's one thing in every show where you go, "Okay, we've landed on something here that's going to help support all the other ideas around it." For us in Patyegarang it was the wall. It represents all the Sydney Basin and the water and the land.